By Alex Fogleman

Kornelis Heiko Miskotte, Biblical ABCs: The Basics of Christian Resistance, translated by Eleonora Hof and Collin Cornell (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2021). Publisher’s Website.

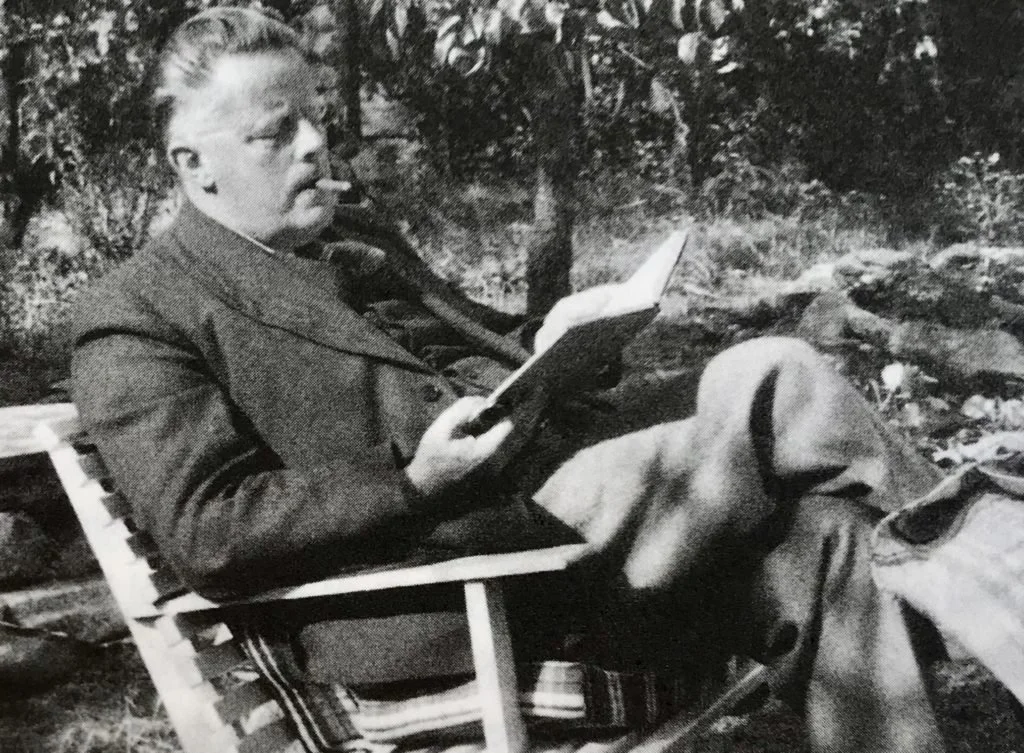

Kornelis Heiko Miskotte (1894–1976) was a Dutch pastor and theologian during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. He began pastoring a small church in 1921 while continuing to pursue academic studies, completing a dissertation in 1932 called The Essence of Judaism. When Germany invade the Netherlands in 1940, he harbored Jewish refugees and participated in underground resistance movements. After the war, he was appointed to a university professorship at the University of Leiden (in 1945). His magnum opus is the book, When the Gods are Silent (translated in 1967) addresses contemporary challenges of atheism, nihilism, and existentialism. He retired in 1959 and died in 1976.

A little known but powerful book—only just now translated into English—is a catechetical text called Biblical ABCs. Originally published in 1941, a year after the Nazi invasion, Biblical ABCs is, as the editors describe it, “a theological resistance primer” and “a refresher course in the basics of biblical language—an anti-Nazi catechism, as it were.” (The editors make no small indication of the significance of the book by beginning their own introduction, written in 2021, with reference to the January 6 attacks on the US Capital.)

Biblical ABCs itself contains twelve chapters—meditations, really—on important biblical terms, such as “teaching,” “the divine name,” “Word,” “Way,” “the Life of the Community.” It is not a standard catechism, in fact, but rather, as Miskotte himself puts it, an attempt to name “the spiritual grammar of Scripture” (3). “Even though the ABCs are not in themselves the essence, they are the grammar necessary to avoid misunderstanding the essence” (6). Scripture is, for Miskotte, the “ground design [grondbestek], the constitution, the model, the frame, the pattern, the fabric and its warp and weft” of the church (5). Scripture is the medium by which we hear the Word of God—the Word of life. And yet in Nazi-occupied Europe, many citizens, including many Christians, could no longer hear the voice of Scripture because they had not learned this basic grammar. “We traipsed one one hallowed hall to another in the ivory tower of the spiritual life … and yet we skipped elementary school” (4).

It is clear that Miskotte sees catechesis as an urgent political task for Christians. And yet, he rarely if ever explicitly mentions the current issues in any detail. This reticence, no doubt, owes to the tight control of speech amid censorship laws. But there’s also something more going on. Miskotte writes: “Many cry out for action. But it could be, that the primordial action is hearing” (italics original). The first step to redressing political fragmentation is to turn to more basic issues. For instance, what is “authority”? In the early pages of the book, we find this:

How do we find true freedom proceeding from authority? … Authority is here identical to that which is authored … It is not forced upon us, but offered to us. It sheds light and draws us to the light. It occupies us, far more than a work of art or a speech. It doesn’t win our heart over through subjugation but through emancipation. Scripture does not rob us of autonomy, but initiates us into a more intense originality. (3)

To help Christians re-learn the spiritual grammar of the Bible, Miskotte addresses the role of the divine Name. The divine Name of God is the “A” of the ABCs (17). For Miskotte, the divine Name is especially significant as a counter to “paganism,” which for Miskotte is code for all forms of natural religion: “the entirety of Scripture is anti-pagan testimony, which paganism is the natural religion of humankind. It takes a thousand forms but reflects a single intention” (4). Here is what he says about the divine Name as a contrast to paganism/natural religion:

The Name distinguishes God from other beings, gods and demons. The Bible does not reckon with a general concept of God, only later to add specific names, images, and qualities. The text speaks first and foremost about God as one god among other gods. (18)

The central place of the Name means that revelation is always a particular revelation—always has been, is, and will be. God has a name: God is not the nameless one. God is not the All, but is known as a reality that distinguishes itself in the world from the world. God does not appear to us as the most general, that which can be found everywhere, but rather as the most unique, that which can be sought and found somewhere specific. This does not mean God couldn’t be the most general and the all-powerful and the omnipresent, but rather that the road to knowledge does not begin with the general. We must follow this road, the road of Revelation, to meet the true and living Godhead. (19)

Miskotte’s theological grammar largely avoids explicitly metaphysical categories, but there is little doubt that he sees the catechism as both entailing and shaping a theological metaphysics. It is certainly Barthian in its rejection of any form of natural categories for divine and human relations. Miskotte wants to point readers towards knowing God only in and through Christ, viewing natural religion and natural philosophy as agents of the “paganism” that has infected the Nazi regime.

Nevertheless, while rejecting all forms of paganism, he emphasizes how a Christ-centered conception of the divine Name does allow us to re-narrate God’s all-pervasive presence in the world—primarily through the sanctifying, the hallowing, of human lives. In his chapter on “sanctification,” we read:

On this account, no domain can be left untouched. God has interfered with humans and their world; and, with another and just as necessary emphasis: God has interfered with this human and their world. If God is a particular God, God is also and as such, Elohim, the Deity! Likewise, sanctification is a particular sanctification, but also and as such, sanctification extends into—well, how better to put it?—life; the world—in totality. (98)

The importance of the church’s response in devotion to the Word forms the theme of the last chapter: “The Life of the Community.” There are churches and their are individuals, Miskotte thinks, but there are not communities devoted to studying the Scriptures and living faithfully together. This last note echoes Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s great Life Together. However, Miskotte’s main reference in this section is Pope Pius X’s 1905 encyclical Acerbo Nimis, which stresses the importance of teaching and learning for faithful Christian witness. Miskotte appeals to Pope Pius’s emphasis that “the chief cause of the present indifference and … infirmity of soul, and the serious evils that result from it, is to be found above all in ignorance of things divine” (quoted on on p. 140).

Miskotte takes away the importance of recovering catechesis and empowering the church again to be a teaching and learning community (142). But unlike the Roman church, as he understands it, the church is not only a teaching body but also a learning one—a community that lives “under the word” (143). In this conception, the Christian faithful move from being mere spectators into participants: “The church is the church by faith in becoming the church, again and again. We do not want to be spectators, we desire that communities transform into participants. Into life! Through the Word! (145)

Miskotte returns once again to the urgent task of patient study of the elemental tenets of doctrine—the ABCs. He does not think no further training is necessary beyond the ABCs. New catechisms must be written, new courses of theological study. Still there is an urgent need to begin again with the basics:

We are persuaded that as a tool, the biblical ABCs must take tactical and factual precedence.…because the road to the epic battle of spirits starts there, and it is the shortest and best-protected. It leads from an anguished defense to a spirited offense (146)

Miskotte’s Biblical ABCs is a wonderful testament to the power of recovering a desire for the basics of Christian teaching—of recovering a biblical imagination for the church as a teaching and learning community. Nothing is more pressing, nothing more urgent, than stopping and listening to the Word: to be a hearer, a catechumen. That is, as he puts it, the first step in the spiritual battle.

CODA: Miskotte Symposium and Collected Papers

A nice addition to this book is the set of papers that came out of a conference after the book’s publication in 2021. This included papers both from historians and specialist in Dutch Reformed theology, as well as leading theologians like Philip Ziegler and Katherine Tanner.

It is clear that the Miskotte’s catechism is not just of historical significance but provides a resource for contemporary theology and catechesis. Susannah Ticciati concludes her paper with this remark:

Miskotte’s biblical ABCs is about the learning of a language. This language … provides the grammar of critical self-discernment (whether individual or communal). More than instruction, it provides the conditions of the possibility of instruction: of the critical pursuit of the truth. This is something we arguably need as much today as in Miskotte’s day. Where we have forgotten how to think self critically—how to reason—we need, not to be taught what to think, but to be taught more fundamentally how to think.

See the conference page here, videos here, and audio here (last checked Jan. 3, 2023). A special edition of the Journal of Reformed Theology (16.4, 2022) published several of the articles, which can found here. These include:

Philip Ziegler, “Kornelis H. Miskotte’s Biblical ABC’s: A Theological Provocation”: “This essay assesses the key theological claims at the heart of the work, reflects critically upon their meaning and significance, and then draws them into converation with a number of current trends and trajectories in current theological research and writing. In this way, the significance of the work in its own right as well as its—perhaps surprising—relevance to the present theological discussion is brought to light.” (From the abstact).

Susannah Ticciati, Katherine Sonderegger, and Christophe Chalamet, “Contemporary Theological Voices Responding to K.H. Miskotte’s Biblical ABCs”:

Susannah Ticciati argues that “Miskotte can provide a helpful critical development of Kathryn Tanner’s thesis of noncompetitive relation between divine and creaturely agency. She shows how Miskotte’s ‘detour’ via the particularity of the divine Name could free humanity from pagan self-deception and transform human beings into responsive and responsible actors.”

Katherine Sonderegger “stresses that by emphasizing the particularity of the divine Name, Miskotte himself comes perilously close to the pagan notion of local, limited deities that early Christians and Rabbis would abhor. Yet, Sonderegger goes on to show how in the Beth Midrash (House of Learning) Christians can learn from the Torah about this radical incarnation as the ultimate rebuke of paganism.

Christophe Chalamet focuses on “the ecclesiological consequences of Miskotte’s biblical theology for the church today. He elaborates on what scripturally learned ‘core groups’ could mean for contemporary Christian renewal.”

Niels den Hertog, “K.H. Miskotte and the Dutch Reformed Churches during the Occupation of The Netherlands”: “This article is about the Dutch theologian K.H. Miskotte and his theologically based resistance against the Nazi occupation regime (1940–1945). The leadership in Dutch churches chose a cautious and often unprincipled approach to dealing with the occupier. Miskotte, along with some others, pointed to a different way. He wanted a better resistance, founded in the Bible. He read the Bible as the testimony of the LiberatorGod who frees his people from slavery to the gods and powers of this world that blind and enslave people. Miskotte’s book Biblical abcs, though created under the challenging circumstances of occupation by a Nazi regime, also points the way for today to a way of reading the Bible that is current and surprising.

Mirjam Elbers, “The Name as ‘Anti-pagan’ Monument: Central Theme(s) in Miskotte’s Biblical ABCs,” focuses on the central theme of the Name YHWH in Miskotte’s catechism. For Miskotte, “Paganism … does not mean the absence of religion nor a particular, polytheistic religion or worldview, but the natural human inclination to declare the existing order sacred. Humanity is profoundly ‘occupied’ and needs the Word, the Name-in-action, in order to be liberated from pagan, religious occupying forces—whether these forces are political, spiritual, military, economical or linguistic. This focus on the ‘anti-pagan’ stance of the Name determines the entire structure of Biblical abcs, its method and content.”

Rinse H. Reeling Brouwer, “K.H. Miskotte’s Efforts toward a Renewed Relationship with Judaism”: “K.H. Miskotte’s dissertation on The Essence of Judaism (1932) at once involved constructing a phenomenological Wesensschau, preparation for Jewish-Christian encounter, and engagements in intra-Protestant disputes. Around the Second World War, Miskotte’s writings simultaneously showed unconditional solidarity with the persecutedJewish people andwarned againstJewish influences on Protestantism. At the end of his life, Miskotte reflected with distress on the book of Rabbi Ignaz Maybaum, The Face of God after Auschwitz, and he returned to his initial judgment on liberal Judaism.

Finally, an in-depth book review by theologian Douglas Harink is included. Harink caputres well the relationship between the work of catechesis and scripture: “But the purpose of the book is not to summarize or unfold the content of scripture, but rather to train Christians and churches how to read and understand it according to its most fundamental patterns and structures, or (in Dutch), its grondlijnen (ground-lines) and grondwoorden (ground-words). Grasping the spiritual grammar, the internal coherence, of scripture (the biblical abcs) is necessary to prevent the cooptation of Bible reading and Bible study into merely personal or group interests. Biblical ABCs lays out descriptively the core structure of scripture according to its own fundamental keywords” (387).