Review of Pilgrim Letters: Instruction in the Basic Teachings of Christ. By Curtis W. Freeman. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2021. 112 pages. $22.00. ISBN 9781506470504

By Alex Fogleman

Pilgrim Letters (Fortress Press, 2021)

One of the hallmarks of great teaching is the ability to simplify complex material without reducing it to the point where it no longer resembles its original form. Many of the best theologians throughout history have described the Incarnation as God’s divine “condescension” to humanity—like a father speaking to his children with words he knows they can understand. In Augustine’s famous work, De catechizandis rudibus, the wise bishop asks his correspondent to mirror his catechesis on Christ’s humility, who, though he was the very form of God, chose to humble himself by becoming human and dying the humiliating death of the cross. What would it look for this kind of pedagogy to guid our approach to catechesis?

A good contender for an answer would be Curtis Freeman’s recent book, Pilgrim Letters: Instruction in the Basic Teachings of Christ. The book is a catechetical dialogue framed in terms of the six topics of “foundational” instruction listed in Hebrews 6:1–2: repentance, faith, baptism, laying on of hands, resurrection, and eternal judgment. Freeman crafts a basic catechism on these six topics (“What does it mean to repent? ... What is Faith? etc.) and then devotes a chapter to each, written in the form of letters from “Interpreter,” a more seasoned guide in the Christian journey, to “Pilgrim,” who is a catechumen just beginning.

Each of the six principles is treated with a theological depth that underlies the warm, graceful tone of the writing. We are introduced to sophisticated theological concepts written in a form that any literate teenager could understand. Faith, for example, is not just a mode of thinking but “more a way of seeing, compelled not by the confidence that we understand but by the conviction that we desire what lies ahead” (22). Eternal judgment is “not only about things that come last. It is also about things that last.” Here is the voice of a seasoned theologian who comes down from the tower and onto the road.

Freeman is Research Professor of Theology and Baptist Studies and Director of the Baptist House of Studies at Duke Divinity School in Durham, NC, who has developed a reputation for his work in Baptist and ecumenical studies—work that highlights both the distinctives of the Baptist tradition and its place within the Great Tradition.

Curtis Freeman, Research Professor of Baptist Theology, Duke Divinity School

This kind of ecumenical Baptist viewpoint characterizes this book as well. The publisher rightly describes the tenor of these letters as “evangelical-catholic, free-church-ecumenical, and ancient-future.” Freeman is clearly writing within the Baptist tradition, even as he seeks to help those within the tradition reach out to the broader and deeper roots of the broader Christian tradition. In these pages, Pilgrim meets saints of the Great Tradition like Tertullian, Augustine, Anselm, Bonhoeffer, and Romero, as well as leading lights from the Baptist traditions—Thomas Grantham, Edward Barber, William Carey, and others. We also meet some of Freeman’s own teachers (as well as students), and local churches, showing that the communion of saints extends not only to a bygone age but to those we encounter on a daily basis.

The topic of catechesis is, perhaps surprisingly, just the right context to make these moves. While many in low-church traditions look askance at the Catholic-sounding “catechism,” there is nothing uniquely Roman about it. Its origins are in the New Testament and in the pre-Nicene catechumenate of the second century. The sixteenth century saw the proliferation of catechisms across all denominations. And in the centuries following, Baptists produced hundreds of catechisms for teaching and instructing the faithful. All of these strands inform Freeman’s book, which will hopefully encourage other Baptists to look more favorably on catechesis and, even more importantly, to take it up in their own churches.

Another feature that will appeal to low-church traditions is the explicit grounding of catechesis in Scripture. Hebrews 6:1–2, again, is the central organizing feature:

Therefore let us go on toward perfection, leaving behind the basic teaching about Christ, and not laying again the foundation: repentance from dead works and faith toward God, instruction about baptisms, laying on of hands, resurrection of the dead, and eternal judgment.

While the New Testament may not clearly define a catechumenate with specific rules of entry and systematic processes for initiation, it clearly knows a conception of basic teaching that is integrally related to more in-depth instruction. This two-tiered model is often conveyed with either an architectural metaphor, as in the case in Hebrews 6’s language of “laying the foundation,” or an alimentary metaphor—infants requiring milk before solid food (see 1 Cor. 3:2; Heb. 5:12–14; 1 Pet. 2:2). It’s worth noting that not all of these images are positive. Both Paul and the writer of Hebrews use this trope to prod their audiences to growth, while 1 Peter warmly encourages the “newborn babes” to crave spiritual milk so that they can grow up into salvation.

In any case, it is clear that at least some kind of two-tiered level of instruction is inherent to New Testament Christianity, and that ought to shape any approach to catechesis today. Catechesis is a thoroughly biblical practice. And we need less low-church skepticism of it in order to make headway in renewing discipleship today.

There are two other aspects of the book that serve—without directly saying so—as an apologetic for catechesis against potential detractors. First is Freeman’s use of the epistolary format. In the style of C. S. Lewis, Freeman writes in the voice of Interpreter to show the catechumen Pilgrim a reliable pathway in the Christian faith. Importantly, he is not Evangelist, Teacher, Professor, Bishop, etc., but Interpreter. He is one who himself clearly stands beneath the Word and serves as one who introduces Pilgrim to it. There is a clear “That To Which” he is pointing.

The epistolary format is also a wonderful reminder that catechesis is, at root, a conversation. It is personal, dialogical. This is not to say that it is unconcerned with Truth, the nature of God, or the hard edges of Christian doctrine and morals. However, the approach here envisions doctrinal instruction within the web of Christian relationship. It doesn’t abstract the catechumen into a mass of potential baptizands—numbers to report at an Annual General Meeting. Catechesis takes place in specific relationships, in specific places and times. While the aim is to draw the catechumen into eternity—“to go on to perfection” in Hebrews’ language—that journey begins in concrete conditions here and now, between real people who are en route together. The epistolary format of the book puts the personal back into catechesis.

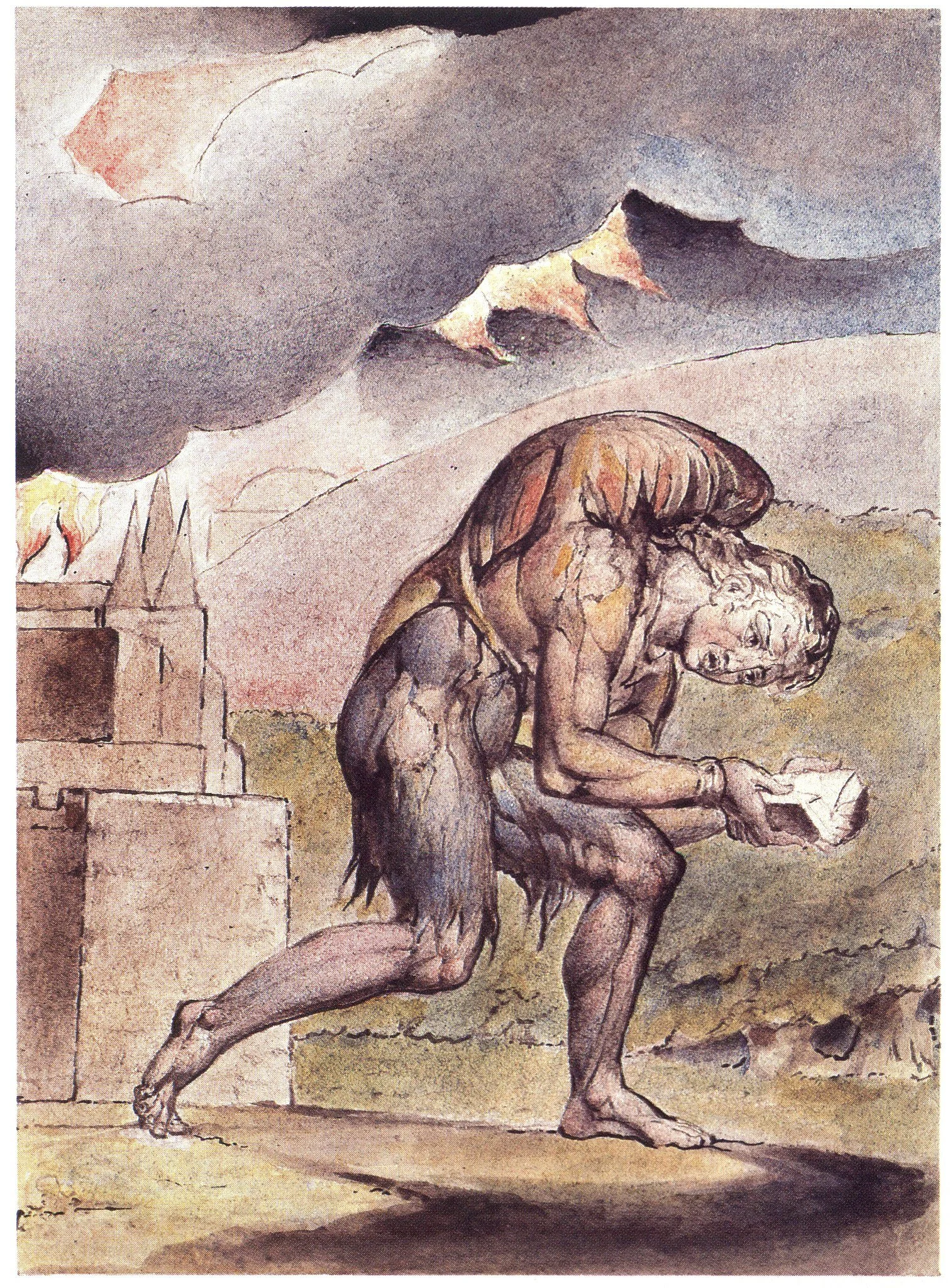

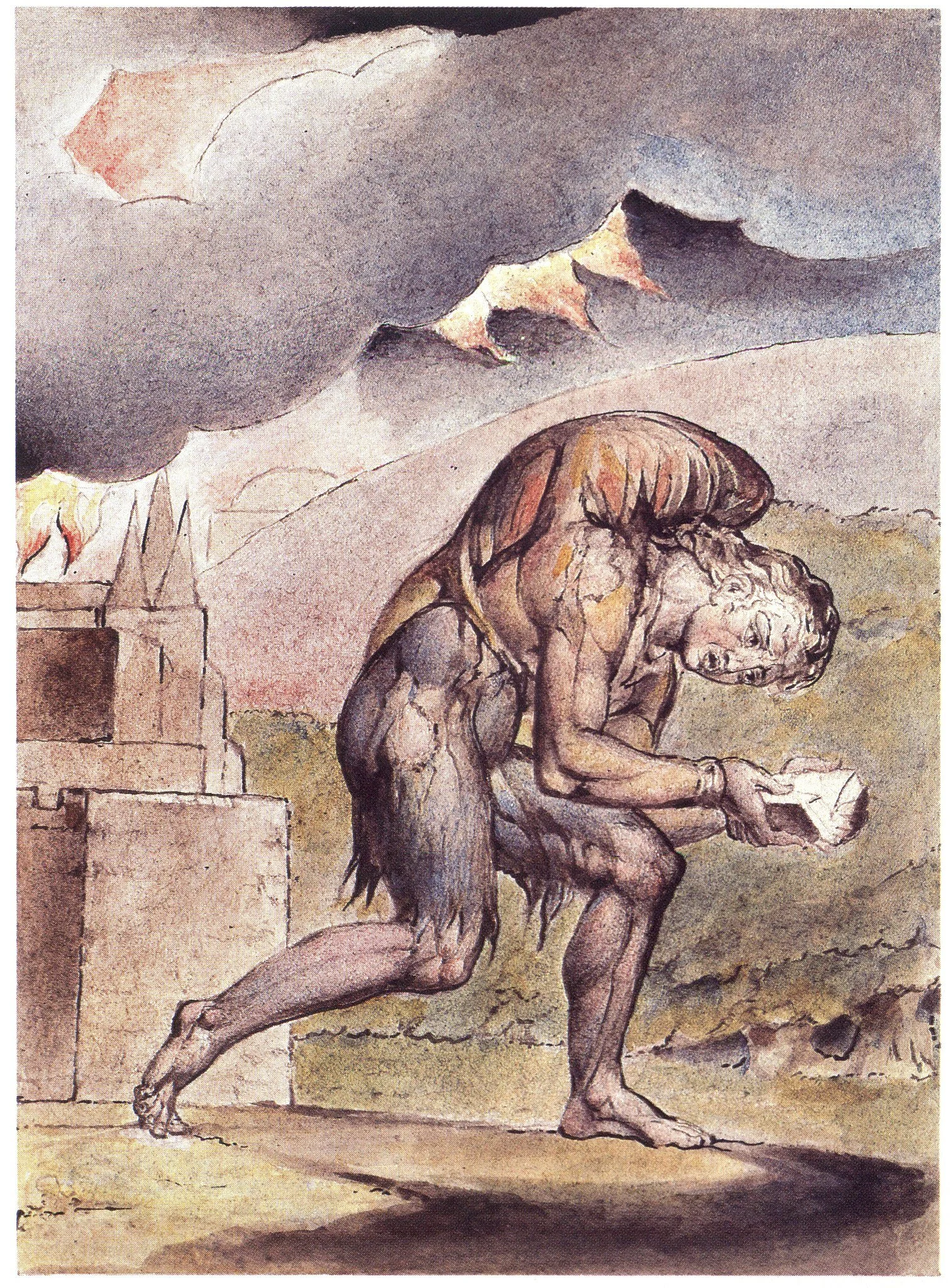

William Blake, Illustrations of Pilgrim’s Progress - Pilgrim’s Burden

Another distinctive of the book is its beautiful use of William Blake’s illustrations of scenes from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Each chapter begins with one of Blake’s drawings and ends with a reflection on that image, exemplifying the main theme from that chapter. In the Introduction, Interpreter explains to Pilgrim that Bunyan’s classic work owes to “its popularity as a catechetical narrative” (8). It was often popular among evangelists, who often translated this work soon after the Bible in the new missionary language. More to the immediate purpose, however, Interpreter wants Pilgrim to allow these images to provide a visual window into the catechetical narrative so that “you might begin to imagine your life in the story” (9).

Like the epistolary format, the aesthetics and narratival character of this book shape its vision of catechesis. These elements demonstrates that catechesis is not merely an intellectual exercise—getting one’s doctrines in order—but about learning to “see” and inhabit the world Christianly. The use of images and historical narrative help Pilgrim see him- or herself as belonging to God’s family and to God’s story. For many, catechesis has gathered a negative association because of its association with an image-less form of Christianity. It is too cold-blooded, left-brained, and rationalistic. However, Freeman’s book does a marvelous job of re-situating catechesis within an aesthetic and narrative framework.

Freeman’s book is a wonderful place to begin the process of catechesis. It would make an excellent book for a pastor, parent, or godparent to read alongside a teenager or adult preparing for baptism—the book’s most natural setting. It would also be a worthwhile read for those who have been baptized but perhaps not actually catechized. The book could profitably be read among a small group or second-level catechesis class. It is not at all uncommon to find oneself in Church for years, even decades, and realize you have no idea what it means to repent, to have faith, to know eternal life. Reading this book with those, both new and old to the faith, could be a profitable way forward.

Speaking of “moving on,” one final salutary aspect the book is its frequent reminder that a good catechesis is aimed beyond itself. As Hebrews exhorts us, we are to “go on to perfection” (Heb. 6:1). We have a tendency to get stuck with a focus on conversion as the end of the Christian journey. The point of faith for so many Christians—especially from evangelical traditions—is to “get saved,” to get converted, to “make a decision.” However, a baptismal theology that aims only for one-time conversions cannot but foster a deficient approach to growing in Christian maturity. We need a catechesis that will set us up for a lifetime of discipleship, of learning obedience to Christ, of ever plumbing without arriving. We need a catechesis that will help us say, with St. Paul, “Not that I have already obtained this or have already reached the goal; but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own” (Phil. 3:12). Freeman’s book—and hopefully others that follow suit—teaches us to say just this.