Zacharius Ursinus, one of the chief writers of the Heidelberg Catechism, on how the Catechism and Theology are prerequisites to reading Scripture.

Rowan Williams has famously written that theology as a discipline is “perennially liable to be seduced by the prospect of bypassing the question of how it learns its own language.” My hope is that this project offers a picture of early Christian catechesis that helps us remember, quite literally, how early Christian theology learned its own language. What it means to know God is inseparable from the ways in which such knowledge is experienced; medium and message are tightly linked. In studying early Christian catechesis, we observe how knowing God belongs within a set of ecclesial practices in which the meaning of knowledge and faith are found in – and founded upon – Jesus Christ. Advancing from faith to understanding, from belief in God to the knowledge of eternal wisdom, begins and ends with Christ.

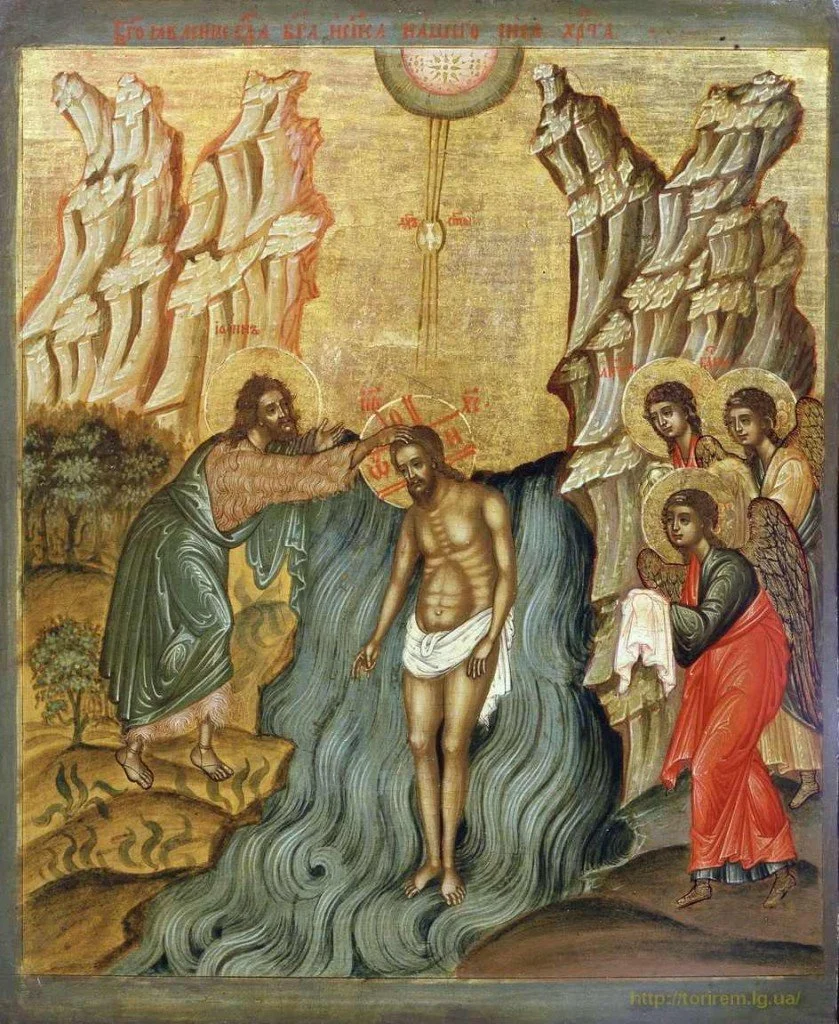

David Lyle Jeffrey on his baptism in the Scottish Baptist Church in rural Canada: “A feature of baptism in our tradition that I continue to value is that it makes you think about the meaning of it quite a lot, both before and after the experience. One of the questions that friends would ask me is, “Do you feel any different?” My Catholic friends especially, since they had the luxury of having just a few drops on their heads when they were too young to remember, wanted to know. Actually, I did feel different, though not perhaps in quite the way they may have expected. It wasn’t euphoric. Rather, I felt as though I had entered into the community of grownups in some way.”

Nicholas Norman-Krause on the Trinity and the Moral Life: “Moral life is not, first and foremost, obedience to a moral law instituted by a distant Lawgiver, but participation in the Triune life by means of deification and sanctification. Law certainly has its place within this Trinitarian moral vision. But, as we will see, law hangs together with other crucial moral concepts within a broader vision of Christian discipleship, of drawing near to the Father, through the Son, by the Holy Spirit.”

Nicholas Norman-Krause on the Trinity and Prayer: “the Lord’s Prayer is only fully intelligible when understood within a larger Trinitarian account of our participation in the divine life. By the Holy Spirit, we are united to Christ, adopted into his sonship, and so enabled to address his Father as ours. And thus, to pray the Lord’s Prayer is to come to participate in the Triune life of God. For this reason, reflection on the Trinity properly belongs to the catechesis of prayer in general, and to the study of the Lord’s Prayer in particular.”

Nicholas Norman-Krause on learning the language of the Trinity: “The doctrine of the Trinity be approached in catechesis not so much as a metaphysical riddle to be solved but as a grammar of speech to be learned. As a kind of grammatical formation, catechesis in the Trinity seeks to bring clarity and coherence to the way Christians worship, pray, proclaim the gospel, and read Scripture. These I take to be some of the primary activities of Christian life, as well as some of the primary ways Christians come to know God. They are also fundamentally linguistic activities, modes of speaking and listening to and with God. Trinitarian catechesis succeeds when it is able to form persons such that their speaking and hearing are sufficiently cultivated so as to know God in these primary Christian activities.”